Newsletter October 2025

Yes, we can prevent violence against women and girls!

The evidence is in: the cycle of violence against women and girls (VAWG) can be stopped. A seven-year, multi-country research and implementation initiative, What Works to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls (What Works II) is now in its fourth year of activity and the results are surprisingly encouraging. We can reduce VAWG dramatically and durably!

Two weeks ago, I had the immense pleasure of speaking to What Works’ Coordinator, Anne Gathumbi, a bold and brilliant Kenyan lawyer and feminist advocate who has worked in this field for many years at the national and international level. She told me why she's hopeful we can stop VAWG.

But first, a bit of history!

Until recently, violence against women and girls was a taboo subject: it was considered a private family matter or a rare occurence, and often something that "bad" women brought onto themselves. The 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the main international treaty protecting the rights of women, doesn’t mention domestic violence, sexual harassment or rape. In fact, you can look in CEDAW for the phrase "violence against women," and you won't find it. Imagine that?! It’s mindboggling.

This silence was finally broken in 1985 at the Third World Conference on Women in Nairobi, Kenya, where for the first time, feminist groups from North and South obtained government agreements in the Nairobi Forward-Looking Strategies for the Advancement of Women to address and prevent VAWG. The 1993 Vienna Conference on Human Rights recognized women’s rights as human rights and its non-governmental forum saw intense discussion of VAWG. This was followed by the adoption by the UN General Assembly of the 1993 Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women and the creation in 1994 of the mandate of UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women.

At the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995, governments went further and agreed that eradicating violence against women and girls had to be a top priority - an entire chapter of the Beijing Platform for Action was devoted to this pressing issue, with many additional commitments in the chapters on Women and Armed Conflict and on the Girl Child. VAWG was recognized as a human rights violation in and of itself, but also as an impediment to the enjoyment of women's other rights, such as the right to health, to education, or to freedom of expression.

The Sustainable Development Goals, adopted by 193 governments in 2015, reaffirmed this commitment to end all forms of violence against women and girls.

Understanding VAWG

These agreements helped spur action by organizations and governments worldwide to better understand the full dimensions of this scourge.

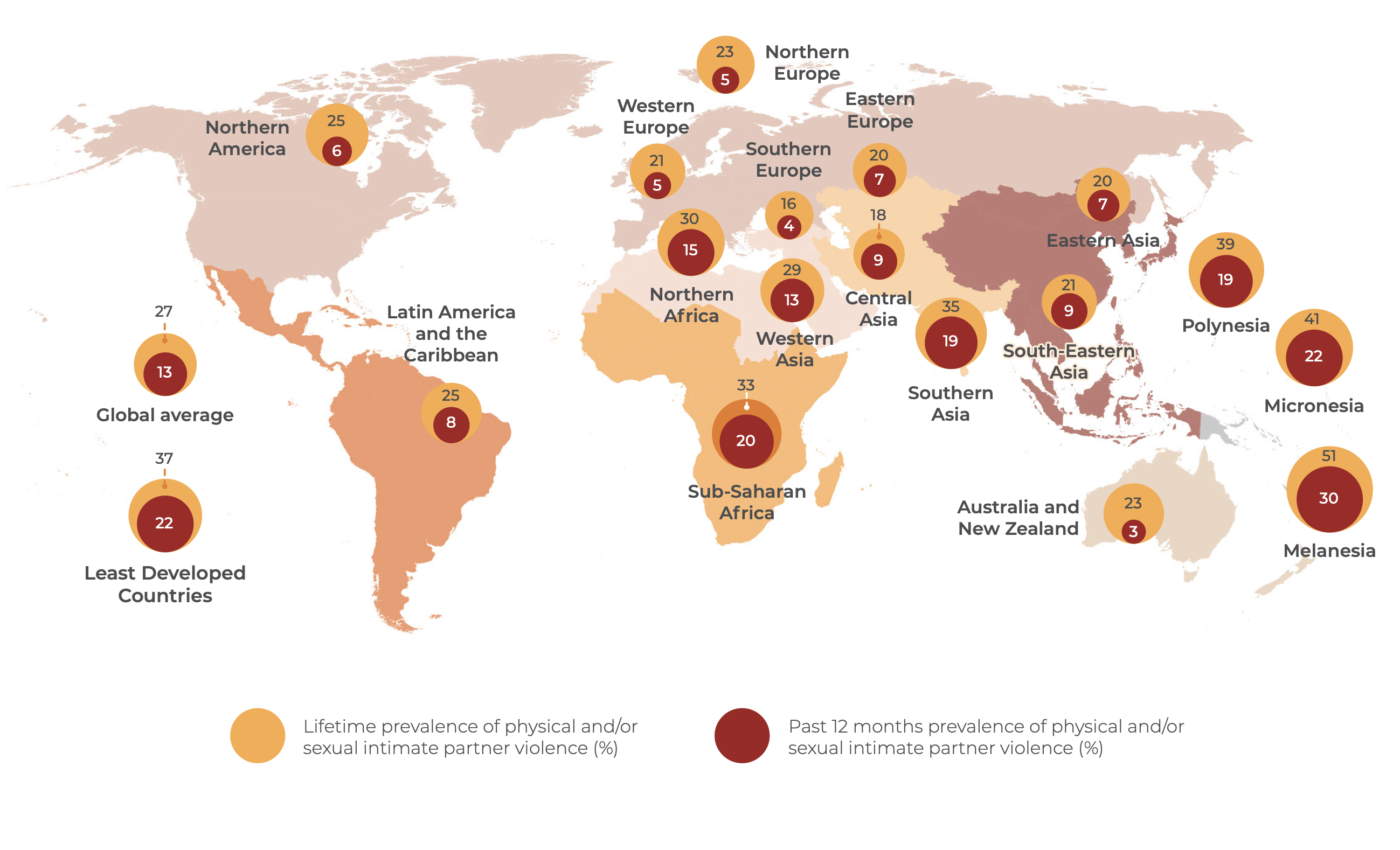

In 2005, the World Health Organization published the first results of a multi-country research on the prevalence of VAWG. Today, the Prevalence Estimates on VAWG cover more than 137 countries. The data confirm that VAWG is a problem everywhere. Across the world, 30 percent of girls and women aged 15 and over (that is, about 736 million girls and women) have experienced physical or sexual violence in their lifetime.

Importantly, this research identified intimate partner violence as the primary manifestation of VAWG. Worldwide, 26 percent of girls and women aged 15 and over have experienced physical or sexual violence from a current or former husband or intimate partner at least once in their lifetime. Intimate violence begins early: worldwide, 24 percent of girls aged 15-19 have experienced violence from a boyfriend or husband. In other words, the most dangerous place for a girl or woman is not a dark alley in her city, but her own home. And the most dangerous person is her current or former husband or boyfriend.

Other data collected by UN agencies show that worldwide every year, 60 percent of women and girls killed intentionally are murdered by their intimate partners or other family members, such as fathers, uncles, mothers and brothers.

Another significant (but hopeful) finding is that prevalence of intimate partner violence against women varies a lot depending on the context and individuals’ own economic, social and cultural situation. For example, in Fiji and Papua New Guinea, the lifetime prevalence for women aged 15-49 is, respectively, a whopping 52 and 51 percent, while in Cuba and the Philippines, it is 14 percent. Women living in poverty, women with disabilities, women from ethnic or racial minorities, gender non-conforming women, and women living in conflict situations are particularly vulnerable to violence.

Importantly, this significant difference in prevalence means that violence isn’t an immutable and unchanging situation, but can be reduced and prevented.

Preventing violence against women IS POSSIBLE, but poorly funded

Yet very little funding goes to preventing VAWG. Protection measures for survivors (shelters, protection orders) are often among the first steps taken to address VAWG, and much remains to be done even on that front. Prosecution of perpetrators is often touted as another approach, even if it rarely happens in reality.

But prevention programs that could stop that violence from occurring in the first place, that would break the cycle once and for all? Evidence generated in low- and middle-income countries for prevention approaches that work in those contexts? Very little funding has been invested in those areas.

A 2023 UN study found that investment in prevention of gender-based violence was a mere 0.2% of overall ODA (“overseas development assistance” or foreign aid) in 2021-2022. Yet estimates indicate that violence against women can reduce a country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by as much as 4% per cent, with violence against children costing up to 5% of GDP. Violence against women costs EU members more than 16 billion euros annually.

Unfortunately, prevention of VAWG sits low on the list of priorities for donors. This is despite the fact that prevention of violence has been found to be far more cost-effective than addressing its consequences. Research conducted in Europe found that every euro spent on preventing violence against women yields 87 euros in savings. In Uganda, the thoroughly evaluated SASA! community program reduced physical intimate partner violence (IPV) by 52% for just $5 per person reached, with $460 of savings per case of violence averted.

To spur action, in 2019, a group of UN agencies under the leadership of WHO published the RESPECT framework for preventing violence against women. It identified the risk factors that should be mitigated (such as harmful gender norms that uphold male privilege and limit women’s autonomy, or experience of violence in childhood/in the family), and the protective actions that can be taken (such as socializing boys and girls to hold gender equitable attitudes and reducing intra-family violence).

Investing in prevention

Given the above, women’s rights organizations called for resources to be devoted to testing and documenting approaches that actually work, in order to finally move the needle on prevention. The What Works initiative was launched in 2013 specifically to do that.

In a first phase of What Works (2013-2019), the UK government invested £25.4 million in 15 countries across Asia, Africa and the Middle East to develop evidence of effective programs. What Works I evaluated 15 interventions in different settings including rural, urban, and post-conflict. The results were impressive, and even surprising: some of the programs durably reduced incidence of violence against women and girls by as much as 50%!

Given these very promising results, the UK government launched What Works II in 2021: this time, £67.5 million is being invested over seven years. Two other donors, Ford Foundation and the (now Trump/Musk-destroyed) U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) joined in for specific initiatives. So far, 14 grants have been awarded to fund a range of approaches in 11 countries. Some are scaling up interventions where there is good evidence (especially but not only from What Works I), to see how to reach more people, especially in a different context or country. Some grants evaluate “innovations” – new ways of preventing VAWG that are promising but haven’t yet been documented. And some seek to mainstream prevention programs withing existing, large government programs and services such as education and health. In a second round, another 12 grants should be awarded.

------------------------------------

Exciting, isn’t it? So, four years on, how is it going? Here are excerpts of my conversation with What Works Coordinator Anne Gathumbi.

FG: At the outset, tell me how What Works defines violence, and women?

AG: We are guided by the international normative frameworks like CEDAW [UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination] and the Maputo protocol [Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, on the Rights of Women in Africa] that have comprehensive definitions of violence. We look at violence in all its forms, whether it's intimate partner violence, sexual violence, emotional violence, economic violence. Also violence in technology, violence in online spaces. Any act that threatens the freedom of women, that deprives women and girls of their rights in private or in public. We also pay particular attention to sexual violence in war and other conflict settings, to see if we can generate evidence in those contexts, because there isn't a lot of evidence on that aspect in terms of what works.

That being said, we have a focus on intimate partner violence in a lot of the programs, because it’s the most prevalent form of VAWG. And we had solid evidence from What Works I on preventing IPV, so we wanted to be able to build on that.

Regarding women, we are intersectional, we are inclusive in our approach and define women as women in all their diversities, be they heterosexual women, lesbian women, cis or trans women. Anyone who self-identifies as a woman. In fact, we have two grants for studies on addressing and preventing violence against LBT (lesbian, bisexual, trans) women [grants that What Works II doesn’t publicize to protect the groups and researchers from… violence].

FG: I saw that What Works identified gender inequality as the underlying cause of VAWG. Can you say more about this?

AG: Before we launched What Works II, we conducted many conversations with civil society, as well as a “barrier analysis,” to understand what prevents women's and feminist movements and women's rights organizations in Asia, Africa and the Middle East from actually being able to tackle VAWG head on. Because there's been money going to VAWG. Yet violence has continued, and we still deal with femicide. Numbers don't change, they get even worse in many places. So we wanted to understand why it doesn’t shift! And women's organizations from the global South pointed to the issue of power, on many levels.

Gender inequality is a root cause of VAWG because we are talking about power. Patriarchy maintains its power through violence or the threat of violence, whether on the home front or at the state level. So we had to address gender inequality if we wanted to stop VAWG. There is no way we are going to reduce violence without shifting gender norms. That was clear.

But women’s rights organizations went further. They spoke about other power dynamics. They were saying, not only is violence itself a power issue, but funding is a power issue, research is a power issue. You're talking about doing research in the global South, which brings in global South-North research dynamics. And when funding goes to INGOs (international non-governmental organizations), we [Southern women’s organizations] are only contracted at the tail end and get the least amount of money. How effective can we be in being transformative?

That’s when we understood we wanted to anchor this program in a feminist analysis. We crafted core feminist principles to guide all of our work.

FG: What do the feminist principles require of you, the donors and partners?

AG: We agreed we needed to center the lived experiences of women survivors of violence in all the work, especially the full range of experiences of those women and girls. And we had to ensure we took an intersectional approach that recognizes the multiple forms of oppression and discrimination that women and girls experience. That's how we actually arrived at how we define women. Trans women experience specific violence because of who they are, and we needed to recognize that.

We also said we want to work in equitable ways. How do we partner as North and South researchers, groups and governments? We don’t want to be subjecting people to a power dynamic that’s extractive, where we use their work and don’t give them credit or visibility. That meant establishing equitable partnerships.

And we prioritized partnering with women's rights organizations. That wasn’t easy because there was this push and pull, about whether women's rights organizations have the capacity to do this kind of research. And we said, how can they not have capacity when they are ones on the front lines every day, dealing with the cases of gender-based violence in their contexts?

And we agreed we would be accountable to women and girls in the global South. Twice a year two global South organizations in the What Works consortium do an independent evaluation and reflection, where they interview our research partners and grant partners, about how they're experiencing this work. Are we centering women and girls in our interventions? How are we sharing power? How are we being intersectional? All those aspects. They produce an annual reflection card, shared with everybody, with recommendations on what we're doing well and need to amplify, where we aren't doing well, and what we need to do less of. It’s been transformative in ensuring we live by our principles.

FG: Are there examples of the work you are particularly excited about?

AG: Yes! Some of the projects are legacies from What Works I. For instance, in Pakistan, What Works I funded a play-based life skills program for male and female students ages 11-15 that build their skills at making decisions and having conversations about consent and respect in relationships. It was found to be effective at reducing violence in that age group, including reducing incidents of bullying. It’s now being rolled out for about 8,000 students in 160 schools in Pakistan by two Pakistani organizations, Right to Play and Aahung [a fabulous feminist organization featured in the Famous Feminist Newsletter in September 2022!). We are already seeing improved gender attitudes, and less depression in the cohort of students.

In Rwanda, What Works I funded a program called Indashyikirwa, a five-month, 21-session (heterosexual) couples-based intervention. The curriculum focuses on values, power, relationships, gender, and decision-making in the household. It was found to be effective at reducing violence and improving communication. It is now being scaled up in Kenya, in a modified version, by two Kenyan groups [CREAW, a feminist organization, and AFEOP (Agency for Empowerment of Pastoralists)].

In Madagascar, where we’re implementing a comprehensive sexuality education program in schools, we’ve found that it does a number of things. It's improving learning outcomes. It's also improving relationships amongst students, stops the bullying and mental health issues in schools, enables girls to access contraception. It's lowering pregnancy rates. All of that!

Communities Care in Somalia, a new model for What Works, engages with adolescents, parents and communities. It is now being scaled in Somalia in communities and in elementary schools by the government and three groups [the Committee for the Development of People (CISP), an Italian international development organization, in partnership with local women’s groups, the Somali Women’s Development Centre (SWDC) and Women’s Initiative for Social Empowerment (WISE).] It delivers a curriculum over four or five months, with trained facilitators from that community leading community conversations on a weekly basis. In the school context, teachers are trained to deliver curricula tailored to age groups of 11-15 and 15-19. Among the topics discussed: social norms about violence, acceptability of violence in your household and in your community, bullying, family honor, virginity of girls before marriage, etc.

One aspect that's really interesting: the Communities Care model was initially implemented in those communities several years ago by the local partners and evaluated by Johns Hopkins University. When we came back to do the baseline [for What Works II] a couple of years after the earlier intervention, we found that the social acceptability of violence had come down and stayed down. People still said, we learned that it's not okay to beat your wife. You shouldn't do some of these things in the name of family honor. And that was a couple of years after the first intervention in that community. So the change was still evident.

credit: What Works to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls/CISP

FG: That’s impressive! Based on what you’re seeing so far, are you confident that changing social norms is possible, even in these challenging environments?

AG: Yes, absolutely. But let’s be clear: social transformation doesn't happen overnight. There's no such thing as a silver bullet! It’s hard work. We know that short-term interventions, like awareness raising, do not deliver results. This can’t be a “one off.” And you can’t just show up in a community and say here we are, we are doing this. You have to invest in building trust! They have to know that what you are there to talk about is actually beneficial to them. And that takes time, just that element of continuity and trust building with communities.

So we have to invest in the long term. And that's why What Works II expanded to seven years, to give us and the partners enough time to implement and learn, so that we can demonstrate it works. The whole point about social norm change is you have to take the long-term view. To achieve transformation, you have to be consistent, maintain fidelity to the model, adapt those models and then monitor and document the results and you have to learn continually from the practice. It’s real work.

FG: What about laws against VAWG, to criminalize the behavior and arrest perpetrators? Can they help prevent VAWG?

AG: We’ve found that laws and policies against VAWG on their own aren’t enough. Of course, they provide a framework, a legal basis for the work. So a lot of organizations have focused on pushing for these laws and policies. But then they stop there, and the laws don't get implemented.

FG: Right. Laws against violence aren’t self-implementing, unfortunately! We know this in the global North too.

AG: Exactly. We found that we have to tackle the issue from many angles. We can’t stop at law reform.

FG: Why was it so important to have women’s rights organizations as key partners on the ground, as opposed to other kinds of groups?

AG: Several reasons! First, we wanted to bridge the gap between practice and research. All this research done by universities usually ends lying somewhere on a shelf. Even the evidence generated in What Works I was not being used. The uptake was not there, because either people didn't know about it, or if people knew about it, they didn't have the funds to take it up. Or even if they had the funds, they might not understand the models very well. They needed someone to take them through, with technical assistance on how to do this in practice.

That’s why working with feminist organizations is critical, because they're the ones on the front lines. They're the ones who are doing the heavy lifting of actually dealing with violence within communities. They have the trust of the communities. They can take up that evidence of what works and implement it - if we support them.

At the same time, feminist groups are also the ones who have been doing lots of work on the ground to stop violence. But they've not had money for research, to test what they are doing and to be able to prove that it also works. Some have been doing mentorship with girls for instance, for so many years, but nobody has ever funded them to be able to document it.

Does it deliver the results? If yes, we need to know that. And so that was an opportunity to document and test that practice and knowledge they’ve accumulated over the years, and prove it really works. That’s what we’re doing with the innovation grants. This will also strengthen the long-time capability of women's rights organizations to deliver these programs. This is very important because the question of “capacity” is always used against them, to deny them funding.

By the way, the duration of funding came up as a big issue. Women’s groups were saying, a donor has funding for a two-year project. You start the project, and before you can even finish the study or even find results, that money is over. So we wanted to be able to invest in women's rights and feminist organizations for at least three to five years, so they can do the intervention and learn from it and be part of telling the story.

In the end, actually, a lot of the funds went to feminist organizations. Feminist organizations even won the large grants, the scale grants!

FG: Ha! They’re so good they will rise no matter what! [laughter]

AG: Right?! Our first big scale grant of £4,3 million went to a consortium of three women's rights organizations in Malawi. That speaks for itself!

FG: You also insisted in partnering with locally-based research institutions.

AG: We did. The knowledge base on violence against women (and a lot of other topics) has largely been driven by Northern-based researchers and Northern-based research institutions.

So how do we change that? Because we do need to change that dynamic! If we are talking about decolonizing knowledge, decolonizing research, equitable partnerships, challenging existing power inequities, what does that look like? And fortunately, it was a key area of concern for our Northern research partners also.

For instance, in Tanzania, where we have a scale grant, we are integrating a violence intervention in a nutrition program where the National Institute for Medical Research, NIMR, is the local research partner. In South Africa, an intervention will partner with the South African Broadcasting Corporation to run a media program on violence amongst young people, with researchers from the University of Cape Town.

In addition, we want to bring in local governments to sustain this work. And there's no way we can involve government without being clear about who sits at the table. You can't go to the Kenyan government or another African government and bring a research institution from the U.S. You would never get their cooperation or participation.

FG: Based on what you’ve found so far, what will it take to go to scale?

AG: In What Works I, effective interventions were delivered on a small scale, or without scale in mind. With this program, we have the opportunity to learn about how to go to scale and do that effectively. We do that ethically, with accountability to the communities, and we also make sure we’re going at scale in a safe manner. Why I’m saying that, is because we've seen some donors that say, oh, SASA! [the groundbreaking community mobilization program in Uganda launched by Raising Voices in 1999; it is the precursor of many other VAWG prevention programs across the world] works, we want to scale it up, but it takes too long. This initial session of investing in community trust-building for over six months is too long. We want results quickly.

People want to cherry pick some elements of a model and implement this piece, but not the other. That can cause harm in a community or a family. What we are saying in What Works II is we don't want to do harm. And what I'm excited about is that What Works II is actually enabling us to learn how to go to effective scale in that ethical manner.

The other thing I’m excited about, is that we’re testing different pathways to scale. What are the different types of scale? Because there's scale that seeks to expand the numbers, how many people are you reaching? That's one type of scale. Then there is what we call “political scale.” What results do we get by working with governments, embedding our interventions in the health sector, in the education sector, in a climate change project? That’s political scale, because you have government involved in this intervention, which can yield much bigger results. This is something we’re testing.

We also want to know, if you combine two models, are you going to get better results? There's a lot of evidence on couples interventions. So we asked ourselves, where do we want to add value to that existing evidence? Interventions that layer different approaches, for example? In Malawi, we have a grant that's implementing the SASA! model, but it's layering an economic empowerment component to it, because we already know that economic empowerment models [like credit programs] on their own, are not sufficient to prevent VAWG. So you have to combine them with something. We want to know if you combine SASA! with this economic empowerment intervention, are you going to get better results, and on what dimension?

And then we also ask ourselves in some interventions, for example the couples curricula, how many people can we reach? And what is it going to cost to scale this up? So if you reach 200 couples and you do your cost effectiveness analysis, then you are able to see, is this the most cost-effective way to prevent violence? For example, in Kenya where they’re implementing Indashyikirwa (the Rwandan model), because of the cost of scale-up, we added a mass communications component, a radio component that's going to help with dissemination of the message. We want to test what happens if we add this component on mass communications: are we going to get the same or better results at a lower cost?

We are layering interventions in some cases like that, where there's already evidence and want to learn more. We want to move the field forward by developing evidence to see whether if we combine approaches, we can actually get bigger impact. That's what we are hoping to be able to achieve.

For instance, when we took Indashyikirwa from Rwanda to Kenya… the two countries are very close to each other. But can we assume the characteristics of both countries are similar? In Rwanda, when the government tells couples to come out for a program, couples show up. Maybe that's why it was successful? So we want to see in Kenya whether that model is going to work, in a society where you don’t have the strong hand of government in people's lives.

And if you take such an intervention to Somalia in a conflict zone, how do you adapt it? And how do you maintain the key elements of fidelity to the model? How do you implement it consistently? We also want to learn, at the end of the day, did it help that we included technical assistance in a program, or should we just have given the money to groups and let them figure it out for themselves?

Government buy-in is also critical. For instance, we are learning in Madagascar and in Pakistan, with school-based comprehensive sexuality education, that embedding government in these interventions is very important for scale. We all know it's not easy to work with governments, you have to work at building relationships. It takes time. But we have to learn how to bring governments into the picture and at what point, so that they buy in early on, and take up their responsibility for ending violence. It's the government’s role to take measures, provide programs to end violence!

So there's a whole lot that’s exciting in learning about going to scale.

FG: With What Works II, are you hoping to influence other funders to invest more in preventing VAWG?

AG: Yes. That's the plan.

[NB. the UN/European Union’s €500 million Spotlight Initiative on VAWG was launched in 2017 to support prevention, survivor services, funding to women's groups and law reform. It aims to grow to €1 billion for work in 60 countries by 2028. Spotlight relies primarily on evidence generated by What Works for its prevention programs.]

But right now I have to say I’m worried. USAID was one of the largest funders of interventions and they’re gone. Cuts in foreign aid from Europe are concerning. The funding in the UK itself is uncertain. We don't know what the world will look like in the next few years, just at the moment when we start releasing results from the What Works II studies.

FG: It’s maddening it’s happening precisely at a time where we know the most we’ve ever known about how to prevent VAWG!

AG: Yes, it’s concerning. My key message is this: Violence against women and girls is preventable. We have the evidence to demonstrate that we can end violence in our lifetime. We just need the will to do it! Let's go.

------------------------------------

In feminist solidarity to finally end violence against women and girls,

FG