Newsletter July 2025

Merci Gisèle! When one woman’s courage challenges an entire system

[Warning: this article is about rape, and includes graphic testimony]

Sometimes, a single person’s courage is enough to begin to shift an entire system. That is what happened in France last year when Gisèle Pelicot decided that the trial of the 51 men who raped her would take place in open court, rather than in closed session. The horrific evidence caused a profound national shock. It prodded French lawmakers to finally move to change the definition of rape after years of unsuccessful struggle by activists, and to move forward with more robust sexuality education after decades of right-wing objections and government procrastination.

The trial began in September 2024 in Avignon in Southern France, not far from Mazan, the village where the Pelicots had retired. The facts are appalling: Over a period of ten years, Gisèle Pelicot’s then husband, Dominique, recruited men online to rape his wife as she laid, drugged unconscious, in the couple’s bed. During those years, as she awoke groggy and confused, Gisèle began to think she had a brain tumor or Alzheimer’s, but no medical exam could find anything. She never suspected her husband of 45+ years, the father of her three children.

Dominique advertised on the online site Coco under the heading: “without her knowledge” (“à son insu”). The men who came were young, old, good-looking and fit, fat and unkempt, married, divorced, single, white, Black or brown. Among them: firemen, truck drivers, soldiers, security guards, pensioners, a nurse, a plumber, a journalist, a DJ. Ordinary French men. Dominique documented it all, carefully cataloguing over 20,000 graphic videos and photos of Gisèle being raped while heavily sedated.

As the "Mazan rape trial" unfolded, the shortcomings of the existing legal definition of rape became obvious. Currently, French law recognizes rape only when there is intention to commit the crime (Article 121-3), combined with sexual penetration or oral-genital contact effected via “violence, pressure, threats or surprise.” (Article 222-23)

In his (it’s usually a “he”) defense, an accused will typically claim he had no intention to rape, that it was a misunderstanding and that the woman had enticed or misled him. Additionally, he'll argue that the act of rape wasn't proven because there was, for example, no violence or threats: she had not fought him off, nor objected. Unsurprisingly, in France as in so many other countries, very few rapes are ever reported or prosecuted, and fewer still (only 0.6% of those reported) result in a conviction.

Anne Bouillon, a French lawyer specialized in women’s rights, in an interview to France24, described the law as built on the presumption that people engaged in sex are de facto consenting. “It’s an outmoded idea, that has at its core the concept of women’s bodies as always accessible.” It also evokes the myth of the stranger jumping out of a bush to attack a woman, when in fact, most rapes are committed by intimate partners or people close to the victim. In Gisèle Pelicot’s case, it was her own husband who orchestrated the crimes.

Rape trials are usually closed to the public in France, out of a well-meaning desire to protect the victim’s reputation and privacy. And in the year before the proceedings, Gisèle Pelicot had in fact kept a low profile. She was horrified by what awaited her. But, as she watched the videos with her lawyers ahead of the trial, she became angry and realized what she had been reduced to, what had been done to her.

In Avignon, the initial line of questioning by the lawyers for the accused relied on the well-worn tactic of suggesting that Gisèle was sex obsessed herself, and a willing party to an elaborate role play. This, even though Gisèle was what lawyers would describe as the “perfect victim”—married, a caring mother and grandmother, a gentle person with a quiet lifestyle, no interest in swinging or sex clubs, and not even conscious during any of it! “I feel I’m the guilty party here, and that the 50 are the victims,” she indignantly told the tribunal on September 18, when testimony began. “I’m being called an exhibitionist ! In the state I was in, I couldn’t answer to anyone. I was in a coma. The videos will show that.”

From that moment on, Gisèle made the choice to blow open the whole trial. She had already decided she wouldn’t hide her name or her face. Now she demanded that all the evidence be presented in open court. These videos and photos were graphic—showing Gisèle completely passed out on a bed or the kitchen table, almost naked, unresponsive and often snoring loudly. The lawyers for the accused objected vehemently, complaining of “voyeurism,” of a “criminal porno naming and shaming” and even pleading on behalf of court decorum and Gisèle’s own dignity. She would have none of it. Gisèle even had to fight trial judge Roger Arata on this question. Arata wanted to show the images sparingly, and only in closed session, because he found them so “indecent and shocking.” In the end, she prevailed.

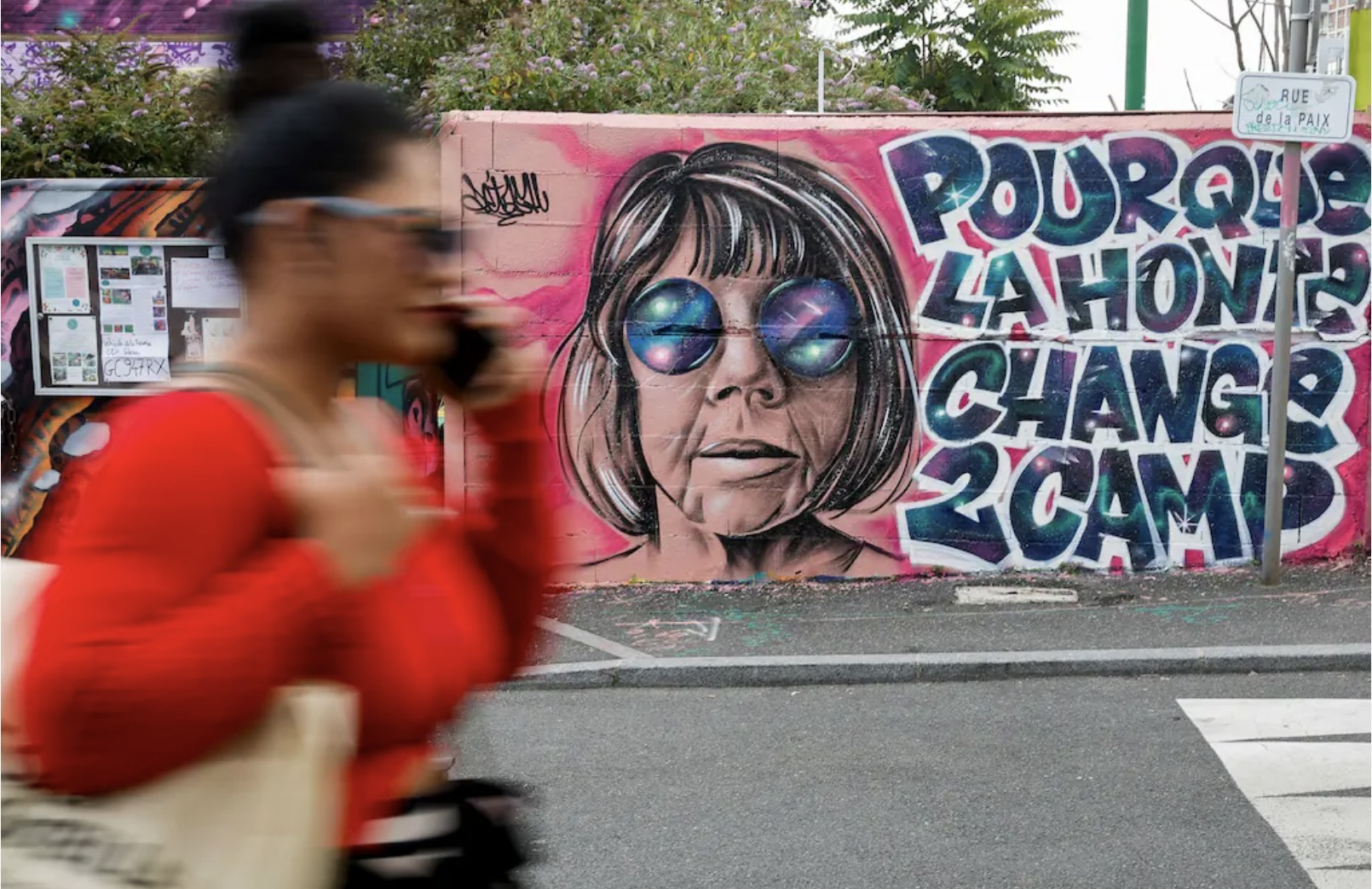

Gisèle’s famous statement: “It shouldn’t be the victims who feel shame, it should be the rapists,” became a slogan: “Shame must switch sides.” (“iI faut que la honte change de camp”).

The trial was undoubtedly traumatic for her. As it began, she testified that “the façade might look solid, but inside, it’s a field of ruins.” The atmosphere in court was described in the press as “morbid,” “crushing,” “unbearable,” with the court personnel looking “horrified” and “in pain,” and members of the public “in shock” and “speechless.” Gisèle persevered, sitting in court every day accompanied by two counselors from Amav-France, a support group for crime victims. She became more determined as the trial progressed, telling the judge “I want women to think, Madame Pelicot did it, I can do it.” She stopped wearing sunglasses and spent time talking to her supporters outside the courthouse.

Without an open trial, it would have been easier for the accused men to proclaim their innocence, and for the press to run with that narrative. The testimony offered by most of the accused makes that clear. I have excerpted some of it below. It wasn’t reported in detail in the English-language press, but it in France, multiple media outlets published it almost verbatim. I haven’t often read press accounts this emotional and this outraged. Seven years after #MeToo, the Mazan trial shook France to its core. For once, the evidence of rape was documented, legible and overwhelming. It offered a grim and shocking picture of a “macho, patriarchal society that trivializes sexual assault,” in Gisèle Pelicot’s own words.

While Dominique Pelicot confessed from the moment he was arrested in 2020 (caught filming under women's skirts in a local supermarket), only 13 of the other accused admitted the facts at the beginning of the trial. The images were used by the prosecution to confront them with the reality of what they had done. (For a start, it prevented them from claiming they had never been to the Pelicot home). But, shockingly, even after the videos and photos were shown, most of the accused continued to deny and deflect.

They testified they had no intention of raping Gisèle. They claimed they were tricked or pressured by her husband or that they thought it was an elaborate sex game. They claimed there was no violence, pressure, threats, or surprise on their part. Others proffered the idea that a husband can authorize others to have sex with his wife. On the stand, one of them even accused Gisèle of deception, demanding angrily that her cell phone be searched, causing the public and judge to gasp.

The defense lawyers’ arguments were equally improbable, and heavily focused on Dominique as the real rapist: “This was a case of fraud. He [Dominique] took them for a ride,” claimed Christophe Bruschi, the lawyer for Joseph Cocco, in an interview to the BBC. Guillaume de Palma, who represented six of the accused, shocked the public when he argued in court that “there is rape and there is rape.” Meaning what? That some rapes aren't so bad? “They did not commit these acts with a full understanding of what they were doing. These were simple men, who were fooled by Dominique Pelicot. Some might even have been drugged themselves,” he added, without evidence. Since the men appeared on video to be lucid and active, and several of them had visited the Pelicot home more than once, these arguments fell apart.

And Gisèle herself? What she had wanted, thought, consented to—all that was an afterthought, if a thought at all.

Read for yourself.

-------------------------

[This is verbatim testimony by several of the accused, as reported by Libération]

“It can’t be me, not given my values. On the videos, it’s my body raping her, but not my brain.” Christian Lescole, 56, fireman, after watching himself on video

“It was described as a game, that’s she’d be sleeping. I didn’t ask myself any questions.” After watching himself on video: “Yes, there, that’s a rape scene, but for me, in my head, it’s not that.” Asked by Gisèle’s lawyer if he was claiming he had raped her by accident, “he replies: “not by accident, but because I wasn’t paying attention.” Florian Rocca, 32, delivery driver

“He manipulated me. He told me that she was taking sleeping pills. Since that was my first time with a threesome, I thought it was a game between them. I didn’t react. I said: why not? But I hadn’t gone there to rape her.” Thierry Parisis, 57, mason

“I thought it was a sex game. I didn’t ask myself any questions. As long as the husband is present, it’s not rape.” Adrien Longeron, 34, construction site manager

“If I’d know I was about to commit rape, I would have said, no, you can’t take my photo!” Patrice Nicolle, 55, electrician

“I have no responsibility for what happened that night. The only thing, is I didn’t ask myself any questions. If I’d know he was filming me, I’d have denounced him to the police.” Joseph Cocco, 69, retired karate instructor (Three ex-policemen testified as character witnesses that Joseph would’ve had all the qualifications to make a great cop.)

“I think at that moment [he went back a second time after Dominique told him Gisèle had liked the first video] I was satisfying the couple more than I was satisfying myself. That may be hard to hear, but that’s that.” Vincent Couillet, 43, carpenter

“I didn’t know she was drugged. She didn’t react at all, it was strange, I told him. I was an instrument, I was fooled. I had no intention of raping her.” Grégory Serviol, 31, house painter, after watching a video of himself masturbating in front of Gisèle’s body and giving the thumbs up

“I was manipulated. I wouldn’t have driven an hour to commit irreparable harm. I am not a rapist, but if I was going to rape someone, it wouldn’t be a 57-year old lady, it would be a beautiful one, I’m sorry.” Ahmed Tbarik, 54, plumber, married for 30 years to his childhood sweetheart

“There was no rape. I was gentle with her, I didn’t hurt her, it went well. If I had intended to rape her, I wouldn’t have let her husband film me.” Redouane Azougah, 40, nurse

“Her husband had given me permission, so I assumed she was in agreement. I didn’t think I had raped her, because I felt OK after the fact.” Andy Rodriguez, 37, unemployed

“I didn’t know that with a finger, it’s rape. I didn’t realize it was serious.” Philippe Lelu, 62, gardener

“It’s her husband who is guilty of her rape. I was used by him like a toy.” Boris Moulin, 37, transport worker

“At no point would I have left my DNA all over [he was not wearing a condom] if I had the intention of committing a crime. At no point was I aware that I was committing a crime.” Mahdi Daoudi, 36, transport worker

“I didn’t ask myself any questions, I was like a guided zombie. I was afraid of him. I don’t know how he got me to come [to their home] six times. Since her husband was there, I thought I had authorization.” Romain Vandevelde, 63, retired, knowingly living with HIV, didn’t use condoms while raping Gisèle

One of the men, Jean-Pierre Maréchal, 63, a truck driver, didn’t want to rape Gisèle. Instead, he asked Dominique to teach him how to drug his own wife, so Dominique could film him raping her, which he did over a period of five years. “Mr. Pelicot was like my cousin. He reassured me. I couldn’t have raped any other woman [than my own wife].”

-------------------------

Whew. It's absolutely brutal to read, and frankly depressing to consider these are, indeed, ordinary men. Gisèle, halfway through the trial, put her finger on it when she said that “it [wa]s cowardice that [wa]s on trial.”

In the end, all the accused were found guilty, with Dominique Pelicot given the maximum sentence, 20 years in prison. The 50 other men were given sentences ranging from one to 15 years of prison, with some of them going free for time served since their arrest. These sentences were lighter than those requested by the prosecution, which had asked for sentences of four to 18 years. Feminist groups that had followed the trial expressed disappointment. Gisèle Pelicot said she respected the tribunal’s decision. Only one of the men is currently appealing his sentence.

The Mazan trial unlocked changes that had been long in coming. On June 18, 2025, the French Senate at last agreed to include the concept of a rape victim’s “lack of consent” in the country’s Penal Code. In April, the National Assembly had already voted on a similar amendment drafted by deputies Marie-Charlotte Garin et Véronique Riotton. They had earlier spearheaded a parliamentary fact-finding mission on rape under the law. A joint parliamentary committee will meet in September 2025 to harmonize the two versions, but a consensus has finally emerged after months of tempestuous public debate. The new definition will require consent to sex to be “free and informed, specific, prior and revocable.”

This new definition will be a significant and welcome change from France’s recent posture on the subject. A couple of years ago, when EU members were debating a draft pan-European law on violence against women, it was assumed the law would include a definition of rape anchored in the absence of consent. This would have aligned it with the definition of rape agreed in the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combatting violence against women and domestic violence, also known as the Istanbul Convention, to which France is an original signatory. But French President Emmanuel Macron and his then justice minister, Eric Dupond-Moretti, worked to block the effort.

And what were the arguments put forward by Macron’s government? That requiring consent would be like “signing a contract before having sex.” Right. We wouldn’t want to take the spontaneity out of rape, would we? Oh, and also that rape wasn’t “of such importance” as to be considered a “eurocrime,” and should therefore remain a national matter. Why then did France join the Istanbul Convention? As a result of this French sabotage (shamefully joined by Hungary, Germany and Poland), rape was entirely left out of the European law on violence against women when it was adopted in February 2024. Yes, you read that correctly! French feminist campaigners and their allies were incensed. By contrast, forced marriage and female genital mutilation were included in the European law. That was a very good thing, obviously, but I note that these are practices generally associated with immigrant communities in Europe. Hmmm.

Macron’s impulsive decisions are by now infamous. In March 2024, he suddenly announced that he had changed his mind and would welcome a change in the French penal code to enshrine consent in the definition of rape, infuriating those who had seen him sabotage the pan-European definition only a month before. But no draft was put forward by his government, and it was only until after the Mazan trial that legal reform picked up steam.

In an interview in Libération, deputy Marie-Charlotte Garin described the Mazan trial as the event that “had decisively shaken up public opinion and caused a wake-up call amongst political leaders,” making law reform possible. Senator Mélanie Vogel concurred, “These kinds of victories depend on the strategic context. The Mazan trial highlighted the culture of rape in our society, how commonplace it can be to round up 70 men withing a 50km radius of one’s home.” Once the Mazan trial opened the door to the idea that sex must be a fully consensual act, it was possible to push for the law to make that clear. The long years of advocacy by groups fighting sexual violence finally could bear fruit. And hopefully, "less than perfect" victims will now see justice too.

Mazan also sped up another reform, one that child rights and women’s rights advocates had been demanding for a long time. In January 2025, the Superior Council for Education (Conseil supérieur de l’Éducation, the advisory body tasked with defining school curriculum in France) adopted a new program for education on emotional and sexual life and relationships (“vie affective, relationnelle et sexuelle”), or EVARS, from kindergarten to high school. This program will cover, in an age relevant manner, topics such as consent, good touch/bad touch, puberty, self-esteem, bodily integrity, sexual health, sexual violence, sexist discrimination and homophobia. Regrettably, in a last minute move to appease the far-right, transphobia was removed from the list of discrimination for classroom discussion.

Sexuality education had been mandated by law back in 2001, but it only required three sessions a year beginning in junior high, and 80% of French schools failed to even provide that minimum. Right-wing political actors fought the change tooth and nail as a threat to “family” and “traditional values.” They claimed sexuality education would make children “turn away from heterosexuality” and would pervert them (c.f. the evergreen trope that it would teach children how to masturbate…). But the Ministry of Education stood its ground and EVARS will be launched in September. 160,000 children are victims of sexual violence every year in France, according to CIIVISE, the French Independent Commission on Incest and Sexual Violence Against Children. In total, 5.4 million persons alive today were subjected to sexual violence or incest before they turned 18, i.e. 8% of the population of France. This reform is a long overdue step forward.

Gisèle Pelicot was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur on July 14, 2025, in recognition of her contributions to fighting violence against women. When praised for her courage and dignity, she redirected the compliment this way: “What I’m expressing above all, are my will and determination that we change this society.” A woman of honor if there ever was one.

Merci Gisèle! In solidarity with all survivors.

FG